- Discovery of the Abu Ballas Trail’s last missing link on Egyptian soil -

- THE ROAD to YAM and TEKHEBET (RYT) -

PART FOUR

1. Advance notice:

In anticipation of forthcoming discussions regarding the further X extension of the Road to Yam and Tekhebet (RYT) X here are some advance brief remarks regarding the speculations about the final destination of this trail XX.

In his paper “The west beyond the west: The mysterious “Werners” of the Egyptian underworld and the Chad palaeolakes” (Journal of ancient Egyptian interconnections. vol. 24(2010) pp. 1-14) Thomas Schneider concludes that the description in the „Amduat, one of the Egyptian guides to the underworld “…was inspired by actual knowledge of the environment of the region to the distant southwest of the Nile Valley, beyond the Gilf Kebir and Gebel Uweinat.” (Ibidem) and that the palaeolakes of Bodele and Fitri in Chad “… “…correspond to the topography of the Anduat” as reflected in this Middle Kingdom mythical narrative. Schneider also considers the region of these two palaeolakes XX…as the destination to which, XX ancient Egyptian donkey caravans X, from the end of the 6th dynasty onwards, XX were heading, in order to obtain high valued merchandise such as incense.

X Schneider´s findings are X mainly based XX on X his interesting linguistic analysis of the terms “Apophis” and “Wernes”, but no hard facts were available to him at the time of his research. X So the validity of his X conclusions would increase if way stations and alamat (road signs) of an ancient trail connecting Gebel Uweinat with the Chad Basin would surface.

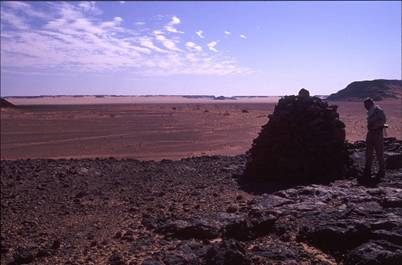

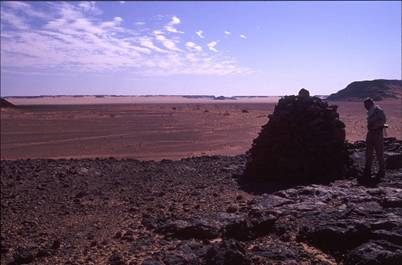

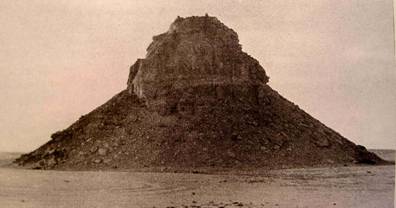

In my book “Der letzte Beduine”, Reinbek 2001, p.376 and on this website (for instance in “Wilkinson´s zweites Zerzura”, September 2002 and in “Discoveries in the Western Desert of Egypt”, August 2003) I had already pointed out that the RYT may indeed lead to the Chad basin. This proposal is now X supported by photographs of a huge alam of, presumably, old age which X had been found by Uwe George and Uwe Karstens on January 27, 1999 in Erdi Korko, northeastern Chad, about 435 kilometres southwest of Gebel Uweinat; approx. position N 190 19.0´ + E 220 7.5. (figures 1 + 2) This alam is situated in a straight line half way between X Uweinat mountain and the palaeolakes in question. Although a detailed investigation of the alam and a search for possible donkey road segments has not yet been performed, it is most likely that the alam shown in figures 1 + 2 belongs to an ancient road which leads from Gebel Uweinat to either Yam or to Tekhebet i.e., to the Chad basin.

figure 1: Old RYT-alam of considerable size found in Erdi Korko, northeastern Chad, about 435 kilometres southwest of Gebel Uweinat. (Courtesy of Uwe Karstens)

figure 2: Close-up revealing construction details of the alam

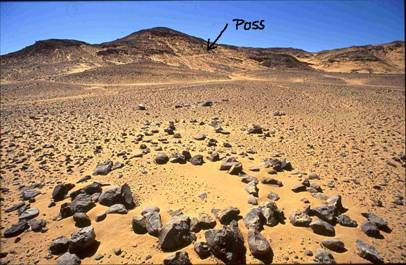

Another feature, already familiar X on the Western Desert leg of the RYT, is the occurrence of colocynths close to the alam and to the supposed ancient road. (figure 3) XX I have argued in my articles “Results of winter 2005/06 + 2006/07 + 2007/08 expeditions” also published on this website, that XX colocynths were used as food for humans along the ancient donkey caravan routes, XX as well as for feed and as a water source for the beasts of burden. About 15 disintegrated stone circles XX in the immediate surroundings of the Erdi Korko alam (up on the flat-topped elevation shown in figure 1) indicate that the place may have served as a muhattah (camp site) whose nearby environment, even today, is capable of producing firewood, grazing and victuals i.e., colocynths for the most basic needs.

figure 3: A field of dried colocynths seen in January 1999 only a stone´s throw away from the alam . (Courtesy of Uwe Karstens)

Sehlis 4/23/2011

Carlo Bergmann

Corrections in blue made on 5/22/2011

Corrections in red made on 8/23/2011. These corrections include a replacement of figure 2 by figure 3 and the insertion of a new image which corresponds better with the caption of figure 3.

- THE ROAD to YAM and TEKHEBET (RYT) -

- my expedition report -

2. Fruitless search for the last missing link of the RYT on Egyptian soil

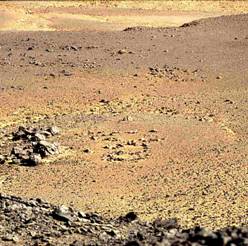

On the 13th of February 1987, whilst on my way from Gebel Uweinat to Farafra Oasis with my three camels Hassan, Atma and Kambyses, I stopped for the first time at Abu Ballas Pottery Hill. Soon after unloading the beasts I climbed the hill and gazed into the gleaming void which, wherever I looked, stretched out unending to the horizon. Here and there a few unnamed elevations rose from the featureless plain. They lent support to the eye bringing illusions of safety up to the moment when I noticed that the desert had swallowed up the faint tracks of my caravan, the only vestiges of life far and wide. I had no GPS in those days. Engulfed in silence and stripped of all sense of place, I felt quite confused about the presence of the three sizable alamat which somebody had erected on top of the hill’s summit plateau. These road signs (figures 1-3) aroused my interest. Were they of old age? Noticed from a far distance in 1917 by Ball and Moore when they were passing by, these alamat had caused the surveyors to deviate from their route and to head for the hill with their cars. Their curiosity resulted in the discovery of “…a large collection of old broken pottery jars marked with the tribal signs of the dark-skinned Tebu …evidently meant for storing water… 120 miles southwest of Dakhla.” (R. A. Bagnold: Libyan sands. Travel in a dead world. London 1987, p. 276) In those days and for a long time after, the significance and impact of the find was not fully realized.

figures 1+2: The three Abu Ballas cairns photographed from two different vantage points.

2.1 Ambiguities regarding the age and function of the Abu Ballas cairns

To me, the design of the cairns was not at all unusual. Anyone could have stacked up stone slabs in such a way. In fact, one of the road signs (indicated by a B in figure 3) looked like a British style cairn commonly used for marking triangulation points. Similarly shaped cairns erected during the Geographical Survey (January 1925 to December 1936) are found further north in the Egyptian desert. However, Abu Ballas hill astonishes visitors because its top contains not a single cairn, but a cluster of three. For any ancient or early twentieth century land surveyor, such a cluster would be superfluous in terms of the normal function of an alam. Furthermore, the arrangement did not conform with my observations made hitherto on the RYT. (see parts one and two of this report)

It is unlikely that the road signs were erected by the Tebu or Bideyat as these desert people, originating in the Tibesti and Ennedi would normally place just a single stone or two if any, and therefore, three chest-high cairns on a bare summit plateau where building material is sparse, would be out of character. Ladislav Almasy used to build alamat necessary for subsequent back bearings (L. E. Almasy: Schwimmer in der Wüste. 2nd edition. München 1999, p. 138) and so did British explorers. (See for example Bagnold´s note of November 18th 1938, which I found northwest of Laqiya Arbain in a cairn that had fallen apart. (See part two of this report, picture 195)) Were the Abu Ballas cairns old and were they erected at the same time? What meaning could be attached to such a configuration? There was no quick reply to these questions. To satisfy my curiosity I measured, photographed and took bearings of the three stone stacks.

Surprisingly,

a.) the line connecting cairn B with the westernmost alam C (figure3) points towards 2230 (430 reverse bearing). This is the direction to Gebel Uweinat i.e., to Ain el-Brins (circa N 210 54´ + E 250 8´) located at 2230 in 382 kilometres distance.

b.) the line linking cairn A with cairn B (figure 3) points towards 1880 (80 reverse bearing). This is, more or less, the direction to Bir Bidi (Wadi Emeiri-East, Wadi el Anag; circa N 190 18´+ E 260 26´) located at approximately 1920 in 582 kilometres distance, to Bir Oyo (circa N 190 18´+ E 260 12´) located at approximately 1940 in 588 kilometres distance, or to Nukheila/Merga Oasis (circa N 190 2´+ E 260 19´) located at approximately 1930 in 613 kilometres distance. Or, even further, to Malha Wells and Malha Crater at 1,041 kilometres distance.

c.) the line linking cairn A with cairn C (figure 3) points in the direction of 2110 (310 reverse bearing) hence, indicating a possible route to the upper reaches of the Depression du Mourdi where, at 755 kilometres from Abu Ballas, a large elongated pan south of a scarp marks a broad passage to the eastern shores of the Paleao-Tschad lake.

Sidenote 1: Later, I noticed that the “B-C reverse bearing” of 430 points in the direction of the Old Kingdom settlement of Ain el Ghazareen/Dakhla oasis.

figure 3: The Abu Ballas cairns A, B and C and their alignment to each other.

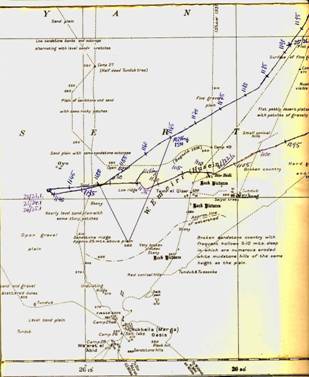

figure 4: Map section showing Nukheila/Merga, Wadi Emeiri/Husein and Bir Oyo including the route which I walked with my camels in winter 1986/87.

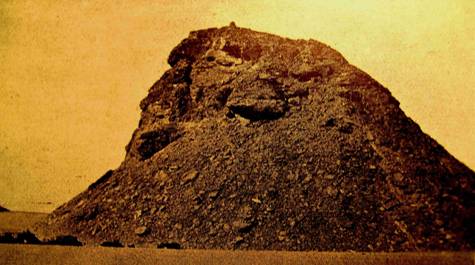

Were these considerations valid? Or was my conjecture false? – i.e., that the Abu Ballas cairns had functioned as geographical direction indicators beneficial for ancient donkey caravans. Hans Rhotert who, together with Leo Frobenius et al., visited Abu Ballas in April 1934, mentions the existence of one alam only. (H. Rhotert: Libysche Felsbilder. Darmstadt 1952, p. 71) But did Rhotert who photographed Pottery Hill from the east, really bother to climb the elevation and to check its plateau? From his camera position only cairn A is visible. (figure 5) Interestingly, a photograph showing the elevation as viewed from the southeast taken almost a year earlier by Hoellriegel on March 26th 1933, shows two fairly well discernible alamat (figures 6+7) i.e., probably cairns B and C. However, on Ball’s photograph taken quite a while after the discovery (but before Hoellriegel and Rhotert) from a position straight south of the hill, only one alam is seen, i.e. probably cairn C. (The caption to Ball’s photo runs as follows: “Pottery Hill from the south: at foot, petrol and water supplies of Prince Kemal el Din´s Expedition of 1923” indicating that the picture was taken after Kemal el Din´s 1923 visit. See J. Ball: Problems of the Libyan Desert. The Geographical Journal 70(1927)pp. 105-128) Hence, is it conceivable that, from Ball’s camera position, cairns A and B were obscured by the southern rim of the Abu Ballas summit plateau? I did not succeed in finding a photo of Pottery Hill taken on the occasion of its discovery in 1917. Because of lack of such evidence it remains uncertain whether or not the three Abu Ballas cairns could be considered ancient.

But, to make some headway, if we assume that, on the occasion of their discovery, Ball and Moore had not erected cairns B and C, and that such work was not carried out by others visiting the site before 1933, both alamat could be very old. Hence, Hoellriegel´s photograph could serve as a proof that nobody had moved cairns B and C after March 1933.

figure 5: From H. Rhotert: Libysche Felsbilder. Darmstadt 1952, plate XXXVI, 1. Detail of his photograph of April 1934 showing Abu Ballas and parts of the expedition’s motorcade as seen from the east. Rhotert writes: “Auf dem Gipfel ein Steinzeichen“. (On the hilltop one cairn. H. Rhotert: op. cit., p. 71.)

figure 6: Pottery Hill from the southeast photographed by Arnold Hoellriegel in March 1933 showing two cairns. (A. Hollriegel: Zarzura. Die Oase der kleinen Vögel. Zürich 1938, p. 48a)

figure 7: Detail of figure 5 showing cairns B(?) and C(?).

figure 8: From J. Ball: Problems of the Libyan Desert. op. cit.: Pottery Hill as seen from the south showing one cairn only.

figure 9: Detail of figure 8 showing cairn C(?).

More than 55 years after Hoellriegel´s visit I photographed Pottery Hill from what I believed to be Hoellriegel´s camera position. My picture not only shows cairns B and C, but also cairn A. (figures 10+11) Thus, either Hoellriegel, using a lens with a different focal length, had shot his photograph from a position closer to the hill which means the view of cairn A was blocked by the south-eastern rim of the hill’s summit plateau, or cairn A did not exist in Hoellriegel´s time.

figure 10: My photograph of Abu Ballas presumably taken from Hoellriegel´s position.

figure 11: Detail of figure 10 showing three alamat.

This meager evidence demonstrates how, at this stage, it is difficult to determine the age of the Abu Ballas cairns and to assign to them a possible function as direction markers that, in ancient times, was already providing information (embodied by at least two alamat) about the trail’s faraway destinations, in particular that of Gebel Uweinat. (Later, I realized that the Mentuhotep inscription discovered by Mark Borda in 2007 is located on the same bearing as Ain el-Brins (2330)).

Sidenote 2: Regrettably, I did not get hold of a booklet which, according to Hoellriegel, Kemal el-Din had published about Abu Ballas (see A. Hoellriegel: op. cit., p. 42), nor of M- L. Franchet´s “Les depots de jarres du Desert de Libye”. Possibly, both works contain images of the Abu Ballas cairn(s).

2.2 Resuming the search for the RYT in 2001: after-effects of my speculations made at Abu Ballas in 1987 and 2000

In January 6th 2001, when my camels and I were resting on top of the escarpment of the southwestern Gilf Kebir plateau (see part two of this report, picture 196), I once again became aware of the vagueness and ambiguity of my calculations presented above. Would my assessments have any potential at all to promote a search for the rest of the ancient trail on Egyptian territory? Or should further endeavors be based solely on geographical data obtained from RYT way stations so far discovered and also from data of a few other relevant sites? According to compass readings taken from my bivouac of 1/6/2011 (see part two of this report, picture 196) these were:

- Balat: 480 at 443 km distance

- Muhattah Maqfi: 480 at 425 km distance

- Meri: 490 at 390 km distance

- Muhattah Harding King: 490 at 347 km distance

- Muhattah Jaqub: 490 at 317 km distance

- Muhattah Umm el Alamat: 490 at 292 km distance

- Bint Ballas: 500 at 268 km distance

- Abu Ballas: 480 at 238 km distance

- Muhattah Fatima: 500 at 174 km distance

- Khasin Berlin: 540 at 95.5 km distance

- Muhattah Rashid: 550 at 87 km distance

- Nearest Kufra Trail water jar: 340 at 184 km distance 1)

- Ain el-Brins: 2070 at 150 km distance

- Bir Murr: 2080 at 148 km distance

- Arkenu: 2330 at 149 km distance

- Erdi Korko Alam: 2210 at 564 km distance

1) waypoint known later

The reverse bearings (i.e., the reciprocal values) of 480 and 550 are 2280 and 2350. Gazing through my binoculars and letting my eyes wander across the vast flat expanse which stretched from below my vantage point to the “Little Gilf”. (see part two of this report, picture 196) I noticed nothing. However, the ancient trail had led my caravan from Muhattah Maqfi all the way to the northeastern rim of the oval depression located in the upper reaches of Wadi el-Akhdar (see part two of this report, background of picture 193). Thus, if the road would maintain its course as indicated by the narrow corridor in which the way stations listed above are placed, it seemed probable that, instead of Gebel Uweinat (i.e., Ain el-Brins located at 2070 in 150 kilometres distance) the RYT could head towards Gebel Arkenu (located at 2330 in 149 kilometres distance).

But why should the donkey caravans of the past have marched constantly within the narrow margins of a corridor regardless of topographical obstacles? So far, the main track of the RYT deviates from its general direction whenever encountering topographic barriers such as the eastern front of the Gilf Kebir which rises circa seven kilometres to the west of Muhattah Rashid. It again alters its straight course when traversing the Gilf Kebir plateau proper as, in this region, the direct passage is blocked by the canyon-like valleys of Wadi el-Maftuh and Wadi el- Bakht.

On the other hand, if the Erdi Korko Alam(?) marked a point along the RYT route (erected on a 2210 bearing), this eye-catching road sign(?), very similar to the one I had discovered at Muhattah Umm el-Alamat (see part one of this report, picture 43), would fall considerably outside the said 2280 – 2350 alignment. Instead, it would line up with the western foot of Gebel Uweinat (i.e., the mouth of Karkur Ibrahim situated on a 2210 bearing at 162 kilometres distance). Hence, would this deviation to 2210 speak in favor of the western region of Gebel Uweinat as the place to which ancient caravans would head before continuing their journey to Erdi and Ennedi? (see Rothert´s conjectures. op. cit., p. 11)

Sidenote 3: Readers should bear in mind that to date, it is not at all clear whether or not the Erdi Korko Alam qualifies for an ancient road sign. Pending the results of further investigations one may also conclude that this stone construction, similar to the Wadi Talh tumulus (see Results of a visit to Gebel Uweinat and two visits to the Gilf Kebir in November/December 2011, chapter 6.111), is a tomb or a cenotaph.

In ancient times Gebel Uweinat was most probably blessed with more natural resources than Gebel Arkenu and thus may also have been more populated than its neighbor during the period in which traffic on the RYT had rolled on. Therefore, would it be reasonable to assume that the ancient road had passed along Gebel Uweinat´s western slopes despite the fact that there exists an easy passage across the mountainous region to the east of the massif’s summit plateau? Very likely, this camel trail, first reported by Almasy (see part two of this paper, picture 197), including its sidetracks were used since times immemorial.

Sidenote 4: The existence of the large storage jars (or potsherds thereof) along the RYT up to Muhattah Rashid would seem to indicate that there where little or no known, natural resources along this section of the route and this probably is one of the reasons for its relative straightness. In areas with more natural resources i.e., the stretch of land between the southwestern tip of the Gilf Kebir and Gebel Uweinat or Gebel Arkenu, the ancient trail would most likely twist and turn between these resources making it extremely difficult to trace it.

The validity of all these conjectures could not be checked from the top of the Gilf Kebir plateau, but only when descending from it. But where was the pass suitable for heavily loaded donkey caravans? A further opportunity to search for the continuation of the road arose in November 2007. However, on the 11/24/2007, ten days after the expedition’s start, Amur, one of the two camels carrying my provisions, went lame just as we were about to enter Wadi Wassa (see Results of Winter 2007/8-Expeditions, Advance Report). I had intended to pick up the ancient road where I had lost it in winter 2000/2001, and to follow it with my camels from the oval pan in the upper reaches of Wadi el-Akhdar (see part two of this report, chapter 1.331) to the assumed pass at the Gilf Kebir´s south-western end. At that point, I imagined the trail would descent from the high plateau and enter the plain.

When, three months later, in February/March 2008, a further opportunity to explore the RYT was offered, I could not leave Cairo where I was hospitalized because of pneumonia.

Sidenote 5: My medical condition including malnutrition and exhaustion were the inevitable consequences of my efforts to save Amur´s life. Confronted with the option to either cut the ailing camel’s throat and to continue with Ashan alone, or to abandon some equipment and slowly walk the handicapped beast the 480 kilometres home, I opted for the latter and gave up my plans.

With the ailing camel in tow, it took 48 days to reach my house at Bir Hamsa/Dakhla oasis. We were short of food and feed the whole way as the distances between our provision dumps were not designed for such dreadfully sluggish progress. As a result, I arrived emaciated and weak but deeply satisfied that this rescue operation, the longest undertaken on behalf of a sick camel that I know of, had come to a happy end.

In the end, Christian Kny, my sponsor, visited me at El Shuruk hospital in order to receive the blueprint for the February/March 2008 RYT-search which, unfortunately, I was unable to attend.

Sidenote 6: Already on 28th Nov. 2007, whilst “on the retreat” with handicapped Amur, I had received a satellite phone SMS from Mark Borda announcing the discovery of a pharaonic inscription including a cartouche at Gebel Uweinat. (see Results of Winter 2007/8 – Expeditions, advance report; part one, picture 1) As, most probably, this fascinating document can be linked to the ancient trade and transport between Balat/Dakhla oasis and the Tschad Basin(?), the issue to which intermediate destination the RYT leads was resolved in favour of a site at Gebel Uweinat´s southeastern foot.

2.3 Christian Kny´s failed Feb./March 2008-expedition

There remained the task of finding that part of the old road and its way stations (Arabic: muhattat) that lies between the Gilf Kebir and Gebel Uweinat. Hence, after the survey of the south-westernmost part of the Gilf Kebir plateau by car, Christian would have to (a) descent from the steep plateau somewhere in the region of the oval pan, (b) to bypass the rock masses via Wadi el-Ahkdar and Wadi Wassa and (c) to pick up the RYT at the foot of the suspected donkey caravan pass. Meticulously sticking to the ancient trail with his hired 4WDs, he, presumably, would be led to Gebel Uweinat by a string of old way stations. Hoping that my speculations could be confirmed I wished Christian good luck.

Kny´s endeavors were not blessed with good fortune. Entangling himself in constant fights with Machmud Marai (his tour operator) the party (including staff and security officer) was later kidnapped by members of the Sudanese Liberation Army at Gebel Uweinat. This tragic event, along with Kny´s erratic work style and lack of systematic investigation, resulted in a failure to produce scientifically exploitable results. Thus, to review and to expand Kny´s modest achievements another expedition was deemed necessary.

3. My search of winter 2008/9: List of selected waypoints in chronological order (3/5/2009 - 3/18/2009)

3.1 Part A: From the Wadi el Akhdar oval pan to the steep donkey pass at the southwestern tip of the Gilf Kebir

The venture which was sponsored by my friend Hardy Böckli took place between 3/1/2009 and 3/19/2009.

On the basis of the clues I had given to him in hospital Christian Kny had indeed found the RYT´s southern ascent from the oval pan located in the upper reaches of Wadi el-Akhdar. When Hardy and I arrived there, we saw his footprints and those of Mahmoud Marai. In parts, the ancient trail is still visible. Every now and then it is marked by alamat. Here is a list of waypoints defining the road.

3.11 Survey on foot from the Wadi el Akhdar oval pan to “dark hill”

figure 12: Google Earth image of the oval shaped pan in the upper reaches of Wadi el-Akhdar with (A) indicating the beginning of the RYT-ascent, (B) indicating the rock art sites discovered by Kny and Marai and (C) indicating the low flat topped hill rising from the pan’s ground where Kuper et al found a few badly weathered petroglyphs.

1.) 3/5/2009: N 23 11.072 + E 25 59.891 (stone circle at the foot of the pass leading out of the Wadi el Akhdar pan, figure 13.)

figure 13: A stone circle found at the foot of the Wadi el-Akhdar pass.

2.) 3/5/2009: N 23 11.032 + E 25 59.930 (the beginning of the trail’s ascent)

3.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.941 + E 25 59.868 (the middle section of the pass; the RYT is well visible, figure 14)

figure 14: The RYT and the oval shaped Wadi el-Akhdar pan.

4.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.878 + E 25 59.758 (View into the oval pan; old cairn erected a few metres north of the trail, figure 15. Note the modern cairn in the background erected by Kuper et al. This cairn is one of quite a few modern stone stacks surrounding the Wadi el Akhdar pan which has disturbed the archaeological information of the region.)

figure 15: View into the Wadi el-Akhdar oval pan. In the foreground an ancient cairn marking the pass. In the background one of Kuper´s modern alamat.

5.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.943 + E 25 54.871 (a collapsed stack of stones)

6.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.719 + E 25 59.087 (a row of stones, two metres long, aligned 1800/1000 i.e., transversely to the trail, figure 16.)

figure 16: A row of stones aligned transversely to the RYT

7.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.445 + E 25 59.561 (the road splitting into several tracks)

8.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.494 + E 25 59.501 (trail visible)

9.) 3/5/2009: N 23 09.886 + E 25 58.659 (low elongated dark hill; figure 17, topped by a cairn; figure 18.)

10.) 3/5/2009: N 23 09.915 + E 25 58.671 (Three stone circles located at the northern foot of dark hill; figure 19.)

figure 17: Dark hill as seen from the north

figure 18: Cairn on dark hill

figure 19: Three stone circles at the northern foot of dark hill

Return to camp.

3.12 Excursus: New rock art sites on the fringes of the oval pan

In a deep valley situated to the southeast of the RYT-pass (see figure 12, arrow B) and extending from the oval shaped Wadi el-Akhdar pan towards the south, more rock art has been found adding to the severely weathered engraving noted by Kuper et al. at the eastern end of a flat topped elevation that rises from the northwestern section of the said pan. (In figure 12 Kuper´s site is indicated by arrow C. It is also shown on the left of figures 14+15. See W. Schön: Ausgrabungen im Wadi el Akhdar, Gilf Kebir (SW-Ägypten). Teil 1. Cologne. 1996, pp. 51, 110) This undated engraving shows a long horned bovine, two dogs, two human figures and two unidentifiable quadrupeds. It thus, possibly attests to cattle rearing and/or hunting activities during some unknown period. (ibidem, p. 110)

Soon after entering the narrow and rocky part of the valley indicated in figure 12 by arrow B, several rock art sites attracted our attention. (figures 20-23) These petroglyphs were discovered by Christian Kny and Machmud Marai.

11.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.441 + E 26 00.094 (group of quadrupeds, figure 16)

12.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.434 + E 26 00.077 (ostriches and giraffes depicted on a stone slab, figure 17)

figure 20: A group of pecked quadrupeds depicted on a stone slab. Image shown is color enhanced.

figure 21: Ostriches and a giraffe depicted on a stone slab. Image shown is color enhanced.

13.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.420 + E 26 00.058 (A severely eroded scene consisting of a horned quadruped, a giraffe and an unidentifiable animal. Note that the quadruped possesses circular horns possibly representing the solar disc.)

14.) 3/5/2009: Depiction of another giraffe found by Christian Kny (no waypoint recorded)

figure 22: Rock art scene consisting of a horned quadruped (centre), a giraffe (to the right) and an unidentifiable animal to the lower left. (Courtesy of Christian Kny) Image shown is color enhanced.

figure 23: Giraffe engraving. (Courtesy of Christian Kny) Image shown is color enhanced.

15.) 3/5/2009: N 23 10.365 + E 26 00.441 (At the canyon-like steep end of the valley Christian Kny and Machmud Marai came to a fairly large pool. (figure 24) The existence of this temporary water source may be the reason why Neolithic hunters decorated a few rock faces and stone slabs further down the wadi with petroglyphs representing game.)

figure 24: Machmud Marei at the water basin found at the very end of the Petroglyph Wadi. (Courtesy of Christian Kny)

One wonders why Kuper and his team working several winter seasons in the oval pan missed out on this artwork.

3.13 In search of the RYT after ascending the Gilf Kebir plateau by car

In Feb./March 2008, Machmud Marai had found a passage allowing his 4WDs to ascend to the top of plateau of the Gilf Kebir. On 3/6/2009 (my son’s birthday) we left most of our supplies behind in the oval pan, headed down Wadi el Akhdar and soon arrived at Machmud´s pass where, with some difficulties, the drivers managed to bring us up onto the plateau where we continued our search for the ancient trail.

Before we reached the hypothetical line connecting dark hill with the southwestern tip of the plateau, we passed by a hill on top of which a conspicuous cairn had been erected. (figure 25) Although three severely damaged stone circles and a stone tool production site (German: Schlagplatz; N 23 09.831 + E 26 00.402; figure 26.) were found at the hill’s northern foot, the cairn is not of old age. Probably, it had been erected by Kuper and his team.

16.) 3/6/2009: N 23 09.797 + E 26 00.401 (Hill crowned with a modern alam; figure 25. Dark hill at 2710 in 2.98 km distance.)

17.) 3/6/2009: N 23 09.831 + E 26 00.402 (Three severely damaged stone circles and a stone tool production site (Schlagplatz) found at the hill’s northern foot.)

figure 25: Modern cairn probably erected by Kuper et al. View towards the north.

figure 26: Three damaged stone circles at the northern foot of the hill crowned with a modern alam.

Eventually, 1.24 kilometres southwest of dark hill (located at a bearing of 470 ) , we saw what I believed to be the first road sign of the RYT.

18.) 3/6/2009: N 23 09.448 + E 25 58.110 (upright stone slab; dark hill at 470 in 1,24 km distance)

From position 18 onwards, despite my request to travel slowly, we were proceeding much too fast and presumably, we missed some RYT cairns. Eventually, feeling that we were loosing sight of our original objective to search for remains of the old trail and to painstakingly follow it, I asked to stop. We left the cars and went looking for such remains on foot but there was nothing save a tiny cairn erected on a low rock outcrop.

19.) 3/6/2009: N 23 08.477 + E 25 57.582 (Small alam; dark hill at 330 in 3.28 km distance)

Circa 70 metres from position 19 I noticed another small cairn. The two road signs(?) aligned to each other 50/2300, point to a hill topped by a cairn. According to his photographs, Christian Kny had reached the place a year before as the furthest (south-westernmost) point of his survey.

20.) 3/6/2009: N 23 08.456 + E 25 57. 552 (Tiny alam)

21.) 3/6/2009: N 23 07.606 + E 25 56.433 (Hill topped with a cairn and ten stone circles, figure 27. Black hill at 400 in 5.67 km distance)

22.) 3/6/2009: N 23 07.574 + E 25 56.447 (Damaged cairn to the east of the cairn shown in figure 27.)

figure 27: Standing on a flat-topped hill with a stone circle settlement marked by two cairns. View into undulating country to the north.

23.) 3/6/2009: N 23 06.453 + E 25 54.464 (Trail visible, turning towards 2450)

24.) 3/6/2009: N 23 05.804 + E 25 53.877 (After Machmud had lost the way, our motorcade ended up at the edge of a deep valley sparsely covered with a stretch of ephemeral vegetation including a few colocynths. (figure 28)

figure 28: View across a wide valley with a stretch of ephemeral vegetation including a few colocynths

Soon after, we got back to the ancient trail.

25.) 3/6/2009: N 23 06.338 + E 25 53. 198 (Four cairns; three grooves of the donkey trail visible)

26.) 3/6/2009: N 23 06.247 + E 25 52.896 (Three stone circles. Whilst the team stopped for another lunch break, I followed the old road which, in this section, is fairly well visible. On this hike I was without camera.)

27.) 3/6/2009: N 23 06.258 + 25 53.065 (Six grooves of the donkey trail visible. Low descent into a rocky pan.)

28.) 3/6/2009: N 23 06.253 + E 25 53.021 (Cairn)

29.) 3/6/2009: N 23 06.042 + E 25 52.731( At the southern end of the rocky pan. The trail ascends to the plateau again.)

30.) 3/6/2009: N 23 05.988 + E 25 52.668 (A row of stones, one metre long, aligned transversely to the trail)

31.) 3/6/2009: N 23 05.781 + E 25 52.431 (Cairn; trail visible)

32.) 3/6/2009: N 23 05.741 + E 25 52.415 (Cairn; trail visible)

33.) 3/6/2009: N 23 05.227 + E 25 51.908 (Trail visible)

34.) 3/6/2009: N 23 04.822 + E 25 51.522 (Trail visible)

35.) 3/6/2009: N 23 04.811 + E 24 51.514 (Enigmatic stone alignment, 35 m long, oriented 1900/100; possibly man-made; figure 29)

figure 29: A stone alignment as seen from the south. Although this enigmatic structure does not bear similarity to the one found at Muhattah el-Askeri (see part one of this report, pictures 47+48) one wonders whether or not the alignment is man-made. If in the affirmative, what meaning could be attached to it?

At this point Hardy et al. had joined up with me. I got back into the car. We headed to the southwestern edge of the plateau and, directly at the precipice, set up our camp (N 23 04.343 + E 25 50.887). Before nightfall I went eastwards for a walk.

36.) 3/6/2009: N 23 04.370 + E 25 50.968 (Sidetrack of the RYT oriented 2030/400)

37.) 3/6/2009: N 23 04.370 + E 25 50.995 (Another four grooves of the ancient donkey trail’s sidetrack)

38.) 3/6/2009: N 23 04.257 + E 25 51.084 (A further groove of the trail next to a large cairn).

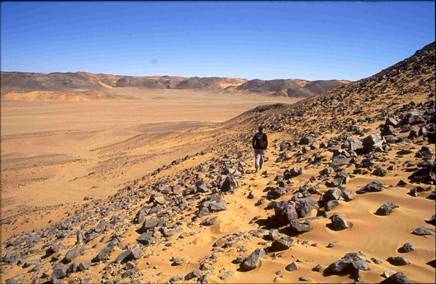

From position 38 it is only a few metres to the eastern precipice of the plateau which, at this point, forms a narrow promontory measuring, east to west, only circa 600 metres only. From the precipice (N 23 04.245 + E 25 51.203) one has a good view into a wadi (marked with (a) in figure 30) extending towards the southeast which, at the time of our visit, was covered with sparse, ephemeral vegetation including colocynths. (figure 31)

39.) 3/6/2009: N 23 04.101 + E 25 51.065 (Cairn probably erected by hunters or handal collectors(?) marking a steep descent(?) at the end of the said wadi.)

3.14 The discovery of the descent from the plateau at the southwestern tip of the Gilf Kebir

In search for the ancient donkey pass I started early next day and walked southwards to the end of the Gilf Kebir plateau. I noticed the following:

40.) 3/7/2009: N 23 04.343 + E 25 50.952 (main track of the RYT visible)

41.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.856 + E 25 51.152 (cairn placed on the flat ground)

42.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.735 + E 25 51.152 (At the southwestern end of the plateau – a view into a tributary wadi of a (see Google Earth image; figure 30) running northeast and covered with sparse ephemeral vegetation (no colocynths).

43.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.710 + E 25 51.118 (Two man-made stone stacks aligned to each other 2140/340, possible alamat indicating proximity to the donkey pass. One of these cairns is shown in figure 32)

figure 30: Google Earth image showing the southwestern tip of the Gilf Kebir plateau with (a) the wadi shown in figure 31 covered with vegetation including colocynths, (b) the position of the descent of the RYT pass and (c) the position of the valley station of the pass.

figure 31: Wadi (a) running southeast and covered with sparse, ephemeral vegetation including colocynths.

figure 32: One of the two stone stacks indicating the end of the plateau. “Rocky Island“ and the conspicuous cone are to be seen on the left.

After a slight descent I followed the trail along the top of a narrow ridge with scree slopes on both sides and reached a rock island that erosion had separated from the main plateau. Here the RYT climbs the island’s low but steep rocky slope until it arrives at its flat top where two, fairly large stacks of stones are piled up.

44.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.643 + E 25 51.171 and N 23 03.607 + E 25 51.190 (two stacks of stones)

To the south of the rock island there is another tiny plateau connected to the “island” by a slightly lower lying mass of rock and debris. Here, at the island’s southwestern foot, I noticed two U-shaped windscreens attached to the bedrock.

45.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.590 + E 25 51.206 (two windscreens; figure 32+33).

46.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.585 + E 25 51.211, (dry stone wall fragments securing the trail’s easy descent from the island.

47.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.549 + E 25 51.201 (A cluster of low stone walls forming four primitive resting places erected at the northern foot of the adjacent tiny plateau, about 70 metres south of the two windscreens)

The two northern and the four southern stone constructions constitute a way station void of pottery, and between them the RYT descents from the Gilf Kebir on a rugged slope. According to my GPS-reading, the plateau, at this point, is circa 1,074 metres high thus, rising about 340 metres above the plain.

figure 33: Windscreens constituting the upper way station of the ancient southwest donkey pass

figure 34: Detail of the windscreen site

I had noticed several trails departing from the foot of the presumed pass towards the plain. (figures 35+36) To find out whether these trails are game paths or routes belonging to the RYT, I had to descend from the Gilf Kebir plateau and to get closer to them. To be sure to have discovered the pass used by donkey caravans of the ancients one must find alamat marking these trails or another way station at the foot of the slope. Meanwhile Machmud et al. had joined up. As Hardy Böckli preferred to stay on the escarpment, Machmud, two of his staff (Eid and Achmed) and I went down the slope. No tracks were visible on the slope indicating that, during the last 4,000 years, the trail was buried by landslides. (Only at the beginning of the descent did I note a single stone placed on a large rock (Steinaufleger) presumably alluding to a person’s urge to mark the proper access to the way down.)

48.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.570 + E 25 51.174 (Steinaufleger at the beginning of the descent)

Further down, after passing the rugged part of the descent, a fragment of the trail finally appeared.

49.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.546 + E 25 51.062 (fragment of the trail)

figure 35: From the top of the Gilf several trails heading from the foot of the pass to the open plain are to be seen.

figure 36: Detail of figure 35

Finally, we reached the cluster of trails shown in figures 35+36. None of them is marked by cairns. Nevertheless we followed the most promising one until we reached a low hill rising from the fringes of a small mud pan where, at the western foot of the elevation, at a distance of 750 metres from the upper way station (figures 33+34), I discovered the “valley station” of the pass.

50.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.434 + E 25 50.786 (Valley station of the RYT pass; figures 37+38)

figure 37: Top view of the “valley station” of the ancient southwest pass consisting of four resting places. Note the tracks meandering towards the open plain and also towards the conspicuous cone topped by a pinnacle that may have served as a natural road sign.

figure 38: Resting places at the “valley station” of the southwest pass as seen from the west.

Although this station consists of nothing but four stone constructions representing simply designed resting places and although, like the upper way station, it is void of potsherds, it provides sufficient evidence that the steep pass which is too difficult to be negotiated by camels, was once used by the donkey caravans of the ancients.

Whilst Machmud, Eid and Achmed returned to the plateau’s top, I followed the cluster of trails which are clearly to be seen in figure 37. These trails are heading towards the open plain, and also towards the conspicuous cone topped by a pinnacle, in a more or less southwesterly direction. Unfortunately, on this hike I found three cairns only.

51.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.246 + E 25 50.454 (A stone placed on a rock (Steinaufleger.)

52.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.043 + E 25 50.367 (A small pile of stones placed on top of a hillock)

53.) 3/7/2009: N 23 03.297 + E 25 50.441 (Steinaufleger found on the floor of a drainage channel.)

Obviously, unlike the careful array of alamat seen on top of the plateau and those all the way from Dakhla oasis to Khasin el-Ali, the absence of similar alignments of cairns, indicates a lack of interest in precisely marking the further course of the RYT. Later, this impression was confirmed after driving along the southwestern corner of the Gilf Kebir plateau via Wadi el-Akhdar and Wadi Wassa and resuming the search for the ancient trail in the area southwest of the donkey pass.

In the afternoon of 3/9/2009, after we arrived in the said area of investigation, I walked from our camp which had been set up at the fringes of the rugged expanse of gravel seen in the background of figure 37 (N 23 00.318 + E 25 47.451), back to the foot of the donkey pass. This strenuous solo hike of almost a day and a half took me across a slightly rising, undulating plain covered with rocks and intersected by numerous small wadis running transversely to my course. I found only a few Steinaufleger i.e., stones placed on rocks, namely at

54.) 3/9/2009: N23 01.114 + E 25 48.637

55.) 3/9/2009: N 23 01.210 + E 25 48.710

56.) 3/9/2009: N 23 01 412 + E 25 48.881

57.) 3/9/2009: N 23 02.584 + E 25 49.814

58.) 3/9/2009: N 23 03.269 + E 25 50.388 and, on the my way back to camp

59.) 3/10/2009: N 23 03. 052 + E 25 50.004

60.) 3/10/2009: N 23 03.338 + E 25 50.570

61.) 3/10/2009: N 23 02.470 + E 25 49. 575

Furthermore, on top of a prominent hillock a toppled stone slab may have marked the way that is no longer visible.

62.) 3/10/2009: N 23 00.057 + E 25 48.044 (toppled stone slab on top of a prominent hillock)

Although markings such as Steinaufleger would qualify as road signs, hardly any remains of the trail itself were visible. In fact, only at

63.) 3/9/2009: N 23 01.636 + E 25 49.053

64.) 3/9/2009: N 23 02.169 + E 25 49. 544

65.) 3/9/2009: N 23 02.455 + E 25 49.770

66.) 3/9/2009: N 23 03.353 + 25 50.608 and, on my way back to camp, at

67.) 3/10/2009: N 23 01.831 + E 25 49.118

did I see vestiges of it.

A reason why ancient travelers may not have adhered to a clearly defined road in this region could be the dominating presence of a huge natural landmark shown in figures 32,33+37. Presumably, this landmark was considered sufficient for providing guidance to the caravans. The landmark consists of a prominent cone with a conspicuous natural cairn on top. It is situated at the southern side of the mouth of the donkey pass wadi and it is noticeable from great distances. Those who relied on it as a point of orientation could have approached the pass from almost any direction thus, avoiding a direct course which would have involved a difficult passage.

Sidenote 7: It should be noted that, in the morning of 3/9/2009 at 6:45 a.m., the cone’s pinnacle was singled out from all other topographical features belonging to the southern front of the donkey pass wadi. It was illuminated first by the rising sun. This silent spectacle suggests that the cone could have served as a beacon for those roaming about in confusion because they had lost their way to the pass.

The unspectacular discoveries made in the area southwest of the donkey pass raised issues that frequently came to my mind as we finally headed towards Gebel Uweinat. For example:

a.) As the survey was confined to a narrow corridor, was I not inclined to associate almost any observation or find with activities on the RYT?

b.) Given that the region concerned may not have been a barren wilderness in around 2,000 BC, being instead likely overgrown by vegetation (steppe grass, tamarisks, acacia and thorn bushes), is it conceivable that the ancients deviated from the direct course so that camp could have been set up wherever grazing and water supplies were available?

c.) Thus, associating a fragment of a trail or a Steinaufleger to the RYT could be mere wishful thinking. Steinaufleger could just as easily have been left by ancient hunters who habitually marked game paths, or even by travelers of the Islamic period.

d.) Hence, would one have to imagine the landscape southwest of the Gilf Kebir differently from what we see today?

e.) Beyond that and given the possibility of a wetter and more vegetated environment in early pharaonic times, were permanent or seasonal settlements of an indigenous population of hunters or cattle herders present in the area during the ancient donkey caravan period, and was this one of the areas the caravans were heading for?

The further south we went, the more meaningful and pressing these questions became to me.

3.15 Further finds made on our way back to the oval pan

On our way back to the oval pan in Wadi el Akhdar Hardy and I left the cars at N 23 06.258 + 25 53.065 (See chapter 3.13, position 27) as, by means of a survey on foot, I hoped to fill the blank area on my map stretching between position 27 and position 21 (hill topped with a cairn and ten stone circles, figure 27) with waypoints relating to the RYT. This short hike yielded a few fragmentary results, such as:

68.) 3/8/2009: N 23 06.336 + E 25 53.198 (cluster of four small cairns; trail visible)

69.) 3/8/2009: N 23 06.369 + E 25 53.252 (cairn; trail visible)

70.) 3/8/2009: N 23 06.377 + E 25 53.313 (large cairn; two further cairns nearby; trail visible)

71.) 3/8/2009: N 23 06.644 + E 25 53.991 (three small cairns(?))

72.) 3/8/2009: N 23 06.739 + E 25 54.194 (trail visible)

73.) 3/8/2009: N 23 06.838 + E 25 54.416 (trail barely visible)

74.) 3/8/2009: N 23 06.959 + E 25 54.718 (trail fragment)

75.) 3/8/2009: N 23 07.213 + E 25 55. 309 (Upright stone slab. From here a shallow playa pan scattered with stone implements stretches up to our destination (position 21))

From this hike and from the observations made before it can be concluded that the concentration of road signs decreases with increased distance from the donkey pass.

When we got out of the cars for a second time, Hardy Böckli found a fragment of a “Darfur type” polished stone axe common in the Wadi Howar area.

76.) 3/8/2009: N 23 08.240 + E 25 57.312 (fragment of a “Darfur type” polished stone axe; figure 39)

This stone axe differs from the grinding stones of the “Gilf type”. (see R. Kuper: Looking behind the scenes - archaeological distribution patterns and their meaning, in: Atlas of cultural and environmental change in arid Africa. Cologne 2017, p. 25) According to Andras Zboray, “this unique find provides conclusive proof that there indeed was a contact between the Gilf and the Wadi Howar in Neolithic times.” (e-mail of 6/15/2009) Such cultural links have been demonstrated by the distribution of so-called caliciform beakers found in the Nile valley, the Gilf Kebir and the Wadi Howar region. However, their dating remains elusive. Whilst one variant of the said beakers was in use at around the 5th and the 4th century BC, another type was associated with the Badari Culture (circa 4,500 BC; see R. Kuper: op. cit., p. 24). The stone axe fragment measures 6.5 cm in length and 5.5 to 5,0 cm in width. The groove’s circumference is 13 cm.

Whilst marveling at the artifact, Machmud´s staff enthusiastically rooted up small pieces of Neolithic pottery scattered across the environs. Nobody could stop them. The guys also found a tethering stone whose exact position is lost. I managed to photograph one of the undecorated sherds and three decorated ones. The thickness of the latter ranges between 0.25 cm and 0.55 cm. From what can be recognized on these tiny samples, their ornamentation which is widespread in southwestern Egypt, roughly resembles the decoration on pottery vessels found in the far away Wadi Howar.

77.) 3/8/2009: N 23 08.215 + E 25 57.337 (undecorated potsherd; figures 39-41)

78.) 3/8/2009:N 23 08.156 + E 25 57.362 (three decorated sherds presumably belonging to the same pot; figure 42.)

figure 39: Fragment of a “Darfur type” polished stone axe common in the Wadi Howar area.

figure 40: Recto of a potsherd found in the neighborhood of the “Darfur type” polished stone axe.

figure 41: Verso of a potsherd found in the neighborhood of the “Darfur type” polished stone axe.

figure 42: The profile of the sherd shown in figures 39+40.

figure 43: Decorated potsherds found in the neighborhood of the “Darfur type” polished stone axe.

figure 44: Colocynths found in the western branch of Wadi el-Akhdar

These artifacts bear witness to the fact that the donkey pass was an important conduit joining for long-distance cultural exchanges between the Neolithic inhabitants of Northwestern Sudan and the Gilf Kebir.

3.2 Part B: The search for the RYT in the lowlands southwest of the donkey pass wadi

On 3/9/2009, my investigation of the RYT had to be terminated. With the exception of a small unsurveyed section extending from a point where the trail descends into a side wadi of Wadi el-Akhdar, northeast of the oval pan (N 23 13 23.0 + E 26 02 26.4; see part two of this report, chapter 1.331) to a point where it ascends at its southern rim (see position 2), a distance of circa six kilometres, an otherwise unbroken trail of about 425 kilometres, as the crow flies, had been reconnoitered and revealed. This ancient donkey trail i.e., the “silk road” of the pharaohs, consigned to oblivion for thousands of years, had connected the Dakhla oasis of the 6th dynasty to the shores of the Paleao-Tschad Lake. Would it be possible in the coming days to trace the remaining part of the RYT up to Gebel Uweinat? Before continuing the survey we drove to the western branch of Wadi el Akhdar where, from a hilltop, I photographed a sizable stretch of green colocynths. (figures 44 + 45) The occurrence of these plants lets one to presume that, in case of need, their poisonous seeds formed an important part of the diet of the ancient personnel of the donkey caravans and also served as forage for the beasts of burden. Thus, as desert and steppe-adapted donkeys are able to quench their thirst from green handal (Arabic term for the poisonous, pumpkin-like fruits of the colocynths), colocynth fields growing wildly in the wastelands, can be interpreted not only as ever-ready natural granaries providing nutriments in an extremely arid environment, but also as seasonal watering places for the animals that frequented such places when traveling along the RYT in ancient times. (For details see several of my Clayton ring reports posted on this website.)

figure 45: Close up of a sizable stretch of colocynths growing in the western branch of Wadi el-Akhdar

We broke up our camp at N 23 00.318 + E 25 47.451 in the early afternoon of 3/10/2009 and continued our search for the RYT in a southwesterly direction. (Readers are reminded that, from this point, I started my hike to the valley station of the ancient donkey pass (position 50).)

79.) 3/10/2009: N 22 57.700 + E 25 46.825 (Cairn consisting of a stack of stones. Neither a trail nor car tracks were visible; figure 46. “Valley station” of the ancient donkey pass (position 50) at 300 in 12.6 km distance)

figure 46: Cairn erected at a flat, virgin expanse of gravel and sand.

12.6 kilometres further on I asked for a stop nearby an inconspicuous elevation. (figure 47) Whilst walking to its southern foot I found a cluster of three rectangular shaped windscreens and a stone circle paved with rocks presumably constituting a RYT way station. (figures 48-50) Note that the cairn found before (position 79, figure 46) is placed exactly half way between here and the valley station of the ancient donkey pass. (position 50, figures 37+38) This can hardly be coincidence. Despite the hill’s low height the muhattah seems to be strategically well placed as, from here, both the conspicuous cone, topped with a pinnacle that marks the way to the foot of the steep donkey pass (figures 33+37) and the peaks of Peter and Paul (at a bearing of 2100) are visible. At the time of our visit the surroundings of the site were void of car tracks.

Measurements:

a.) Main section of the camp (figures 49+50; orientation 1750/3550)

- Windscreen: 4 x 1½ metres

- 4½ metres to the west there are three linear alignments of stones and a stone circle “paved” with rocks (Note that, when a tree to suspend water skins (Arabic: girba) was not available, paved stone circles were used for the temporary storage of these items. Girbas are made of hide. If they are laid on sandy ground they rapidly loose their content due to the effects of osmosis.)

b.) Separate section of the camp (figure 48; orientation 2350/550)

- single rectangular windscreen: 3 x 2½ metres

80.) 3/10/2009: N 22 51.786 + E 25 43.951 (RYT way station consisting of three rectangular windscreens. Valley station of the ancient donkey pass (position 50) at 290 in 25.2 km distance. Peter and Paul just visible at a bearing of 2100.)

figure 47: A low unspectacular elevation harboring a RYT way station. View from the south.

figure 48: The way station’s eastern part. In the background the scarp of the Gilf Kebir. View from the west.

figure 49: Main section of the ancient campsite consisting of (A) a stone circle paved with rocks partly covered by sand and (B) + (C) linear alignments of stones constituting two badly disturbed temporary resting places.

figure 50: Another view of (A)

Soon after, we ran over a few faint fragments of the ancient track coming from the muhattah.

82.) 3/10/2009: N 22 50.731 + E 25 42.458 (Fragments of the old trail oriented towards 2100.)

In the late afternoon, about 42 km south southwest of the donkey pass (position 50), my comrades insisted on diverting from our corridor of observation and to head towards a motorcade of tourists. Regrettably, this unwanted distraction caused me to loose my orientation and wiped out the train of thought that was piecing together the ancient travel & transport modalities that had prevailed in this part of the desert. The region concerned is strewn with sand and numerous low rock outcrops which makes it difficult to trace any trail and now, at N 22 44.158 + E 25 38.424, we entangled ourselves in small talk with strangers. To make the best out of the unpleasant situation, I went on foot in search for road signs and a possible way station which, according to my calculations, could be hidden somewhere in between the outcrops. In the meantime Machmud at al. set up camp (N 22 43.167 + E 25 57.559). I found nothing but a large vertical stone slab placed(?) at the southern end of the obstacle-cluttered terrain. It is doubtful if this slab qualifies as a RYT alam.

83.) 3/10/2009: N 22 42.581 + E 25 37.520 (large stone slab in upright position)

Next day, further confusion persisted as the cars were traveling much too fast for an in-depth survey. At half past nine I gave up my search. We diverted from the planned course and headed for the “Unnamed Plateau” (also named “Little Gilf”). Half an hour later, we entered a shallow wadi with scant, dried up low shrubs including colocynths. (figures 51+52) Next to a granite boulder Hardy found a dead moufflon (Arabic: waddan; figure 53). This find and others of waddan skeletons which I made earlier in the region of the Gilf Kebir (see previous reports on this website) indicate that, every now and then, after a rainy winter, a chain of vegetation links the Gilf Kebir via the Unnamed Plateau with Gebel Uweinat and the Ennedi thus, allowing big game to advance to grazing areas situated as far as Wadi Abd el Malik. According to Machmud Marai, in December 2003, the shallow wadi abounded with green handal.

84.) 3/11/2009: N 22 38.601 + E 25 29.440 (Scant vegetation, numerous mouse tracks nearby dry handal; figures 51+52.)

85.) 3/11/2009: N 22 38.572 + E 25 29.957 (dead waddan; figure 53)

figure 51: Little Gilf, Shallow Wadi. Scant, dried up low shrubs including colocynths.

figure 52: Little Gilf, Shallow Wadi. Detail showing mouse tracks and mouse holes next to dried up colocynths indicating that mice feed on handal.

figure 53: Little Gilf, Shallow Wadi. Skeleton of a waddan partly covered with wind-borne sand.

Heading south we followed a low barrier of dunes and passed by a few isolated bushes. Well before the conspicuous but unnamed mountain that, according to sheet 10 of the British map of 1942, is 1114 metres (above sea-level) high (hereafter referred to as elevation 1114), we arrived at an area scattered with granite hillocks, colocynths and acacias. (figure 54) This was the fifth place during this trip where we had come across the poisonous plants.

86.) 3/11/2009: N 22 35.208 + E 25 27.824 (Expanse scattered with granite hillocks, acacias and colocynths. Figure 54.)

figure 54a: Little Gilf. Sparsely vegetated area including colocynths north of elevation 1114. Elevation 1114 to be seen in the background.

The unexpectedly widespread presence of recent vegetation makes us mindful that, at around 2,000 BC, the area between the Gilf Kebir and Gebel Uweinat was much more densely covered with plants and trees and that, what we see today, is only a sad shadow of its former abundance. Presumably, the crews of the ancient caravans had no problem finding feed for their donkeys nor victuals and water for themselves in this dry savannah. This assumption appears to be duly established by the absence of Abu Ballas type water jars or potsherds thereof in the area and also by the absence of Clayton rings southwest beyond the point where the RYT reaches the eastern flanks of the Gilf Kebir. (Note that this dearth of artifacts is in stark contrast to the assemblages seen at RYT way stations northeast of the Gilf Kebir and also at DWM and Biar Jaqub.) Instead, what has come to light south of the Gilf so far, is a simple stone circle paved with rocks (position 80, figures 49+50) commonly used for a safe over-night storage of girbas. Obviously, there was no need for “long term” water repositories as there was enough rainfall in the area to enable the survival for man and beast. Needless to say, the necessity for the use of Clayton rings as handal pip roasters in such an environment did not exist, as this technique was suited to zones where water was not available. (see figure 54b and previous reports on Clayton rings posted on this website) In areas where water is available the processing of poisonous Colocynth kernels for human consumption could have been executed by means of a laborious method involving fairly large amounts of water. This method reported by Gustav Nachtigal (see Results of Winter 2005/6-Expeditions, postscript of 9/4/2006 and also G. Nachtigal: Sahara und Sudan. Vol. 1, Berlin 1879, pp. 128,129) is still in use in the Tibesti today. If the time-consuming “Tibesti-method” was prevalent on the RYT south of the Gilf Kebir, this could account for the lack of a definite line of road signs marking the ancient trail and, so far, indications of a road have emerged only once and only for a short distance. (position 82) It seems likely that, as soon as the caravans of the ancients reached the area currently under investigation, they slowed their pace, diverted from their direct course and with relief(?), roamed the region in search of water and grazing after having quickly traversed the fearful void of the extreme desert extending between Dakhla oasis and the eastern slopes of the Gilf Kebir.

figure 54b: A Clayton ring shown in operation during an archaeological experiment. The item has been filled with dry, poisonous & bitter Colocynth kernels which are covered by a lid in order to assure an oxygen poor environment. To achieve good results i.e., poison reduced or poison free food, the temperature has to be controlled by removing or by adding embers. A chemical analysis sponsored by my friend Hardy Böckli shows that, with the help of this method, the poisonous properties of the roasted pips were reduced by up to 85% (For details see Results of Winter 2010/11 Expeditions, A solution of the Clayton ring problem (continued)).

Sidenote 8: On his 1930/31-desert expedition Patrick Clayton found two Clayton rings circa 220 kilometres east of Gebel Uweinat at an altitude ranging from 415 to 440 metres above sea level. A sketch map of Egypt’s Western Desert and Northern Sudan made by Riemer and Kuper in 2000 shows 19 additional Clayton ring sites. (H. Riemer, R. Kuper: Clayton rings: enigmatic ancient pottery in the Eastern Sahara. Sahara 12(2000) p.92) To this map I could easily add another 15 places of discovery if not more. So far, not a single Clayton ring was found in the plain bordered by the southwestern slopes of the Gilf Kebir, the eastern fringes of the Unnamed Plateau and the northern periphery of Gebel Uweinat. According to Google Earth the area concerned lies between 750 and 830 metres above sea level thus, considerably higher than any region where Claytons were found. Therefore, it is likely that the topographical features of the landscape concerned i.e., its altitude and the fact that the said plain is located at the edge of high plateaus and mountains, created favorable climatic conditions which, unlike in regions even further south (such as Wadi Shaw where two Clayton rings were found), brought forth a comparatively lush vegetation and a sufficient number of water holes and wells facilitating a modest human life in the wilderness even at times when the RYT was in use. Hence, in the absence of a life-threatening environment, Clayton rings may not have been considered essential items needed for the survival of people roaming or traversing the region.

We spent the rest of the day at elevation 1011 which Hardy and some members of our crew climbed.

Next day, all but Hesham, one of Machmud´s drivers, and I left for the Borda Cave (CC21). The reason for us staying behind was a survey by car of the area between waypoint N 22 38.499 + E 25 35.515 and the minefields at Peter and Paul. We found only weak evidence of the ancient trail i.e., a single Steinaufleger. When reaching the barbwire that fences in a minefield closing the gap between the conspicuous twin mountains (Peter and Paul) we gave up our search and joined the rest of the team at CC21.

87.) 3/12/2009: N 22 32.031 + E 25 31.102 (Stone in upright position placed on top of the northern end of a small hillock.)

88.) 3/12/2009: N 22 24.314 + E 25 25.773 (At the fence of a minefield; figure 55.)

figure 55: Hesham standing at the fence of the minefield which extends between Peter and Paul. View to the south.

At Little Gilf I had injured myself when falling from a huge granite bolder. In addition to suffering from a quite large laceration at the hip I was also afflicted by nausea, fever, chills and pain. Therefore I had to stay in our camp set up about 1½ kilometer from CC21. Only once during our 1½ days stay did I manage to drag myself to the rock paintings.

CC21 is “…a large shelter under a sandstone ridge bordering a volcanic hill south of Peter and Paul, with the ceiling completely covered with paintings of the cattle pastoral period. Both the state of preservation and the exceptional artistic quality qualify this site as one of the most important rock art localities in the central Libyan Desert.” (A. Zboray: Rock art of the Libyan Desert. 2nd edition, op cit.) Surprisingly, the shelter lies fairly well within the hypothetical corridor spanning the steep donkey pass (at 280 in 85.8 km distance) via the newly found muhattah (at 270 in 70.6 km distance) to the site of the Mentuhotep inscription (at 2120 in 57.5 km distance). Hence, despite what has been stated above with regard to the caravan’s possible diversion from the direct course, the ancient Egyptians could have stopped at CC21 using the site as a muhattah which, around 2000 BC, may still have been frequented by an indigenous population.

Kuper et al. classify the pottery found at the Gilf Kebir in three categories

- Gilf A phase: c. 8,000 - 6,600 calBC

- Gilf B phase: c. 6,600 - 4,400 calBC

- Gilf C phase: c. 4,400 - 3,000/3,500 calBC

and, according to a statistical evaluation, associate the low number of Gilf C phase pottery found at Wadi Sura with the low number of rock art images of the cattle herder’s style found in the same area suggesting “…that the herder’s rock art can largely be affiliated to the Gilf C phase.” (R. Kuper, H. Leisen, H. Riemer, F. Förster et al.: Wadi Sura, Field report Season 2009-2, p. 19) Would this suggestion hold true for pottery and rock art of the region between the southern Gilf Kebir and the northern fringes of Gebel Uweinat, in particular for CC21?

Whilst I was recuperating in camp Machmud´s staff scoured the area for artifacts which, later, they brought to our tent. No waypoints were taken. I managed to photograph some of the items. (figures 56–61)

figure 56: From the surroundings of CC21. A mace head or bracelet? Inside diameter 3-4 cm, outside diameter 8 cm: 5 cm thick)

figure 57: From the surroundings of CC21. Decorated potsherd, recto. It is 0,5cm thick and, along the engraved vertical line, 2.55cm wide whilst its max. height is 2.5 cm.

figure 58: From the surroundings of CC21. Decorated potsherd, verso.

figure 59: From the surroundings of CC21. Three decorated potsherds, recto. The sherd on the left is decorated with a Herring Bone design of dotted impressions which, according to Kuper et al., indicates a Gilf C phase (4,400 – 3,000 calBC) provenance. Hence, the item may have been manufactured by cattle herders. It measures 3.4 x 3,6 cm and is 0,6 cm thick. The sherd on the right measures 4.6 x 3 cm and is 0.55-0.6 cm thick.

figure 60: From the surroundings of CC21.Three decorated potsherds, verso.

figure 61: From the foot of the ascent to CC21. Decorated potsherd, recto. 0.7-0.65 thick. According to a TL-test the sherd is 5,600 +/- 20% old i.e., dating to 4,720-2.480 BC; mean value: 3.600 BC.

figure 62: Two fragments of a bowl found at Dune field 2009/10-1 showing a Herring Bone design of dotted impressions which, according to Kuper et al. indicates (a) a Gilf C phase (4,400 – 3,000 calBC) provenance and (b) that the item belongs to the cattle herders manufacture of pottery. Kuper´s chronological estimate is confirmed by the human skeleton to which the pot was assigned as a grave good. The skeleton yielded a C14-date of 4,230 – 3,975 calBC. (see also my Report on the results of radiocarbon datings from the Wadi Sura area, table 1 and figure 11 in: Results of Winter 2009/10 Expeditions)

The potsherd shown in figure 61 resembles the Gilf B phase (c. 6,600-4,400 calBC) sherd decorated with dotted impressions shown in the Wadi Sura field report, season 2009-2 of R. Kuper et al., p. 18. However, this B phase pottery cannot be associated with the pottery manufacture of cattle herders. Although Kuper et al. remain discrete about the population responsible for the production of the said artifacts (produced during the period between 6,600 and 4,400 BC), it is likely that such items were made by hunter-gatherers. Yet, the CC21 imagery does not contain any image that could be assigned to phase B and thus, to hunter-gatherers.

Both, the potsherd on the left of figure 59 and the sherd seen in figure 62, show a Herring Bone design of dotted impressions which may be associated with a fairly similar Gilf C phase (4,400 – 3,000 calBC) potsherd published in the Wadi Sura field report, season 2009-1 of R. Kuper et al., p. 17, figure 16-2, indicating an affiliation to the cattle herders´ manufacture of pottery hence, originating from the same period as the art work in the Borda Cave.

These findings allow to us to draw the following preliminary conclusions:

a.) Following Kuper et al., the potsherd shown in figure 61 resembles the Gilf B phase (c. 6,600-4,400 calBC) decorated pottery. However, its TL-age (circa 4,720-2.480 BC, mean value: 3.600 BC.) correlates well with the time span assigned to the Gilf C phase (4,400 – 3,000 calBC) thus, coinciding with the rock art production of the cattle herder period. Their artwork exclusively covers the ceiling of CC21. As TL-dating yields only imprecise results (see previous comments made on this website) doubts are raised as to whether the above TL age determination is correct. So, if the said TL-age is questionable, would this imply that the settlement at the foot of CC21 was already occupied during the period of 6,600-4,400 BC, and that, during this span of time, inhabitants refrained from creating rock art?

b.) As shown by the potsherds depicted in figures 59+62, the CC21 rock art was produced by cattle herders who frequented the occupation area at the foot of the Borda Cave between 4,400 and 3,000 BC. Hence, the ancient Egyptian donkey caravans would have arrived one millennium after the last inhabitants or visitors to this settlement had disappeared. So who built the four stone circles paved with rocks near CC21? (figures 63+64. Note that one of the stone circles could have served as the floor of a hut.) They are placed at the fringes of the sizable occupation area sprawling across the plain that extends to the west of the rock shelter. Presumably the filled stone circles were built around 2,000 BC in order to prevent girbas from leaking as, 1,000-2,000 years before i.e., between 4,400 and 3,000 BC, more favorable climatic conditions may not have necessitated such a mode of water storage within the confines of a large settlement. (Similar to the scene shown in figure 65 images known from Wadi Sura and Gebel Uweinat show bags and girbas being suspended from the ceiling of rock shelters and hemispherically shaped huts, whilst in other instances girbas are portrayed on their own as well as in the hands or under the arms of individuals. Only in figure 51 of Pantheon-part one (see Results of Winter 2009/10 Expeditions) do we see an object resembling a girba or a bag hanging(?) at the branch of a tree.) Or did Egyptian caravans, if they ever camped at the foot of CC21, use already existing stone constructions? Only a thorough archeological investigation can answer these questions.

c.) These considerations urged me to search for remains of resting places containing pottery indigenous to the region and, at the same time, contemporaneous with the period during which the traffic on the RYT had rolled on. If such occupation sites were found it could prove that, when they reached the region of CC21, the ancient Egyptian caravans where already meeting and enjoying the hospitality of locals who, according to the customs of the steppe/dry savannah, supplied them with the necessities of life.

figures 63+64: Western surroundings of CC21. Two examples of stone circles paved with rocks probably used for the temporary storage of water skins.

figure 65: CC21. Rock painting showing, inter alia, bags or girbas suspending from the ceiling of a hemispherically shaped cattle herder’s hut.

At the request of the discoverer of CC21, the waypoints of the site and of the stone circles close by are not revealed here.

Sidenote 9: Nine months later, on 12/8/ 2009, I finally succeeded in identifying a Late Neolithic occupation site with indigenous potsherds i.e., not of the Abu Ballas type. One of the sherds TL-dating to 640 BC – 240 AD indicates that during this unexpectedly late period, people were still roaming or even inhabiting the Peter and Paul region through which the RYT passes.

I was on a 4WD-tour with Uwe George, Uwe Karstens and Dominik Stehle. Whilst my friends enthusiastically photographed the CC21 imagery, Khaled Khalifa, our tour operator, took me to a hillock (figure 66) situated just 6.6 km north of CC21, where he had found an undecorated rock shelter and a number of potsherds. (figures 67-71) Apart from the sherd shown in figure 71, none of the specimens are more than 0.7 cm thick.

figure 66 : Khaled´s hillock as seen from the south. At the eastern side of the elevation there is a rock shelter which is not seen in the photograph. Scattered across the floor of this shelter and also across a stretch of bedrock in front of it, that has been spared by drifting sands, are a number of potsherds, stone implements and ostrich eggshells.

figure 67+68: From the eastern foot of Khaled´s cave. Five pieces of pottery, recto (left) and verso (right).

figure 69: This potsherd is the only decorated item shown in figure 67. It yielded a TL-age of 2,200 +/-20% years hence, its date range extends from 640 BC - 240 AD, giving a mean value of 200 BC.

figure 70: From the eastern foot of Khaled´s Cave - a potsherd of unknown age, seemingly decorated with a pattern of enigmatic impressions resembling script. To the untrained eye, this artifact resembles a fragment of an ancient clay tablet on which a text in a foreign language has been inscribed i.e., alien to Egyptian hieroglyphs. But it is quite inconceivable that at around 500 BC, diplomatic messages similar to the Amarna tablets (dating to the reigns of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten (1,402-1,334 BC), had been carried along the RYT. Rather than the cluster of impressions shown here qualifying for a written text, these “signs” merely represent a random outcome of pottery decoration made by a stamping technique current among illiterate stone-age people.

figure 71: From the eastern foot of Khaled´s Cave. Undecorated potsherd of comparatively large thickness (1.3 cm)

Because of financial restrictions only the potsherd shown in figure 69 could be dated. According to a TL-test this sherd is 2,200 +/-20% old i.e., as stated before, approximately dating to 640 BC – 240 AD (mean value 200 BC). By any measure, such a date does not correlate with the Gilf C phase (4,400 – 3,000calBC). Instead, the artifact most likely originates from the transition period, during which donkeys were presumably replaced by camels for long distance travels along the RYT.

(a) The 640 BC early limit of the above time span overlaps by a significant measure into the reign of Psamtik I (First king of the 26th dynasty; 664 – 610 BC.) Note that a stele from Dakhla oasis dating to the 10tha and 11th year of the pharaoh’s reign celebrates Psamtik´s victories over Libyan marauders. This text could indicate that, in the period around 640 BC, besides other regions, the desert to the far west and southwest of Dakhla had been of considerable interest to the ancient Egyptians. Thus, it may well be that the tiny item shown in figure 69 provides proof of a temporal and spatial overlap between an indigenous population roaming the “transit zone” (R. Kuper et al.: Field report 2009-1, p. 9) between the Gilf Kebir and Uweinat and the last ancient Egyptian trade caravans that had employed donkeys as beasts of burden.

Yet, for reasons set out before, it is beyond my means to have the provenance of the said potsherd thoroughly clarified. Note however that the most numerous ceramic remains of pharaonic activity found on the RYT so far, date to the Old Kingdom and to the First Intermediate Period. But there is also evidence from other periods namely, the Early Dynastic Periods, the Second Intermediate Period, the late 18th dynasty, the Ramesside Period, the Roman Period and the Islamic Period (F. Förster: With donkeys, jars and water bags into the Libyan Desert: the Abu Ballas trail in the Old Kingdom/First Intermediate Period. p. 1+2; see also (c)). Therefore it should come as no surprise if an indigenous pot or potsherd or even one of Dakhla manufacture dating to the 26th dynasty emerges as far southwest as the Peter and Paul region.

(b) The mean value of 200 BC computed above relates to the era of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt. During the period of 237 – 57 BC the Horus temple of Idfu was built. It contains the so-called oases text, the only document in ancient Egypt explicitly mentioning the seven western oases. Historical facts scattered throughout this primarily religious document indicate that the Ptolemies took an interest in exploiting the modest wealth of these oases. However, merchandise from Yam and Tekhebet is not mentioned. Does this mean that, during the period concerned, the RYT had fallen into oblivion?

(c) The later date of the tested potsherd i.e., 240 AD, would place this artifact in the era of Roman rule in Egypt. With regard to this period, ceramic evidence has been procured on the RYT, so it would be quite reasonable to assume that episodic camel expeditions to the regions far southwest of Dakhla had taken place. As evidenced by two Kufic inscriptions which I found at Muhattah Jaqub (see part two of this report, picture 159 and Results of Winter 2005/6 – Expeditions, chapter E. Supplement: Note on Islamic relics on the Tariq Abu Ballas (TAB) and on the story of the city of brass in “The Thousand and One Nights”, pictures 67+68 posted on this website), such ventures continued until well into the Islamic period.

Imagining the environment that might have prevailed during the period to which the potsherd shown in figure 69 has vaguely been assigned, and imagining also the movements of humans in this landscape, it is quite conceivable that, at a point no further than south of 220 30´ latitude, Neolithic herders of the region may have met with ancient Egyptians and, later, after the Arab conquest, also with Egyptians adhering to Islam who, advancing from the northeast, occasionally passed through their ephemeral pastures. (Note that, according to a recent study on pollen and charcoal preserved in deeply buried sediments in Egypt’s Nile Delta, ancient droughts occurred at four different times between 3,000 and 6,000 years ago, with a mega drought at circa 2,200 BC and two other large droughts between circa 3,500 and 3,000 BC. A further drought occurred around 1,000 BC. (see July edition of Geology or http:/www.upenn.edu/pennnews/researchers-penn-usgs-and-smithsonian-augmentclimate-…) Although these events had a sustained effect on the Nile valley and other North African and Middle Eastern civilizations apparently, the traffic on the RYT was only briefly interrupted. Hence, after periods of standstill, the “lost” information about the route surfaced again and facilitated the resumption of long distance desert travel.)

89.) 12/8/2009: N 22 21.177 + E 25 25.305 (Khaled´s cave; CC21 at 1790 in 6.6 km distance)